The Royal Pharmaceutical Society Becoming the Royal College of Pharmacy: What Would it Mean for Pharmacists?

- The Royal Pharmaceutical Society is required to promote the interests of pharmacists. The Royal College of Pharmacy would be required by law to act for the public benefit. The loss of representation of pharmacists’ interests is significant.

- Pharmacists would no longer have a professional (representative) body if the change goes ahead.

- If the definition of a profession set out previously in Dale and Appelbe’s Pharmacy Law and Ethics is correct, “pharmacist” would cease to be a profession.

- Pharmacists would lose control over material aspects of the way the organization is run. For example, the organization's most senior board, the Board of Trustees, would determine the regulations which make up its own constitution. It could be comprised partly or wholly of non-pharmacists, and RPS members would not be able to prevent this. The same applies to the “Senate” – the proposed replacement for the RPS Assembly. The Board of Trustees could decide that the Senate, including the role of President, would be comprised of unelected non-pharmacists.

- The most senior board – the Board of Trustees – would be able to introduce associate membership categories, for example of pharmacy technicians and dispensing assistants. Pharmacists would have no power to prevent this.

- The RPS’s assets, accrued by members from contributions made since 1841 and used for their benefit, would effectively be appropriated, gifted to charity and repurposed for the public benefit.

- Set against the disadvantages, the potential advantages of the RPS becoming a royal college are, at best, limited.

In Whose Interests Would the Royal College Act?

A good starting point is to examine the RPS’s current royal

charter, which sets out and governs how the RPS must operate as an

organization. The RPS’s entire approach and ethos is determined by the objects defined

in the charter.

The first object listed in the charter is: “(1) to

safeguard, maintain the honour, and promote the interests of pharmacists

in their exercise of the profession of pharmacy” (Emphasis added).[1]

This primary object clearly requires the RPS to act in the

interests of pharmacists.

If the RPS becomes a charity and a new royal charter is

adopted, that obligation will cease to exist. One of the legal requirements for

charity status, set out in the Charities Act 2011, is that the organization

must operate for the public benefit[2]

(see ss.1(1)(a) and 2(1)). If the organization becomes both a royal college

and a charity, this overriding requirement will dictate how the organization

operates.

In practical terms, this means that the RPS – an

organization that acts in the interests of pharmacists – will be replaced by

one that acts in the interests of the public. There are already many such

organizations. For example:

- The Department of Health and Social Care has a duty

to act in the public's interest.

- The General Pharmaceutical Council, as a regulator,

must prioritize public interests.

- The NHS is mandated to operate for the public's

benefit.

- Numerous public and consumer groups also advocate

for the public.

In contrast, there are few organizations solely dedicated to advocating for pharmacists, and only one which functions as the professional body (the RPS).

The RPS first

published the draft version of the proposed new charter on 12 February 2025. It

can be seen in the tracked changes version that the current primary object, which

requires the organization to promote the interests of pharmacists, has been

deleted.[3]

The draft proposed charter makes clear that the royal

college would be yet another body promoting compliance (alongside

employers, the GPhC, the NHS, the MHRA and others.) It would transition from

being a body which serves the interests of its members to an organization which

expected those members to comply with its diktat. Article 4 of the proposed

charter provides that the college’s powers would include:

“(2) to promote compliance with good practice and

the law, and to establish and promote professional standards amongst healthcare

professionals engaged in the practice of pharmacy;”. (Emphasis added).

The charter does not define what is meant by “healthcare

professionals engaged in the practice of pharmacy.” If the Board of

Trustees were to interpret this as including pharmacy technicians (whether or

not this is correct is a separate issue), it would then be setting standards

for them as well. Over time, some would be likely to argue that this should

entitle pharmacy technicians to membership.

No Longer a Professional Body?

I use the term “professional body” as shorthand for

“professional representative body”—an organization that represents the

interests of the profession and provides a voice for it.

The Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain (now

operating under the name Royal Pharmaceutical Society) has long been recognized

as the professional body for pharmacists, providing them with a voice. While some

may take the view that it fails in this role on occasion, that may well reflect

a problem with its leadership rather than its charter—the document that governs

its obligations. It does not reflect a problem with the provision in the RPS’s

charter which requires it to promote the interests of pharmacists.

There are other organizations that act—or at least are meant

to act—in the interests of pharmacists. If the RPS were to become a royal

college, there would be nothing to prevent another body from taking the RPS’s

place as the professional body. However, this is not part of the RPS’s

proposal, nor is it suggested in any other proposal, and nor has it been

discussed by the profession. The RPS has not identified any organization that

would take on the role of representing pharmacists’ interests if it transitions

to a royal college.

A royal college may instead label itself a “professional

leadership body” or similar, implying that it acts professionally and holds a

leadership role, and indicating that it is an organization. However, this

terminology introduces a subtle but significant shift in meaning. There is a

material difference between a “professional body” (as defined above) and a “professional

leadership body.” A professional body represents the profession, whereas a

professional leadership body could lead anything while acting

professionally. Almost any pharmacy organization could call itself a

“professional leadership body.”

Since the term “professional body” can be interpreted in

different ways (I have defined it above for the purposes of this article), some

may even argue that a Royal College of Pharmacy would still be a “professional

body”, without clarifying what they mean by the term. They might claim that the

label is appropriate simply because the royal college would be a “body”

expected to act “professionally.” However, I would suggest that generally

pharmacists are familiar with the term being used in relation to the RPS, an

organization which represents their interests. This presents a risk: the term

could be used misleadingly in relation to the royal college to suggest that it would

continue to operate in the interests of pharmacists, or that the RPS’s

representative functions would remain unchanged.

No Longer a Profession?

In Dale and Appelbe,

at the time it was edited by J.R. Dale and later Joy Wingfield and Gordon Appelbe, a section

outlined the four essential requirements for status as a profession. One of

these requirements was having a “representative body of practitioners,” and the

Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain (RPSGB) was specifically

identified as fulfilling that role. Under the heading “The Profession of

Pharmacy,” it stated:

“If the characteristics described are accepted as the

elements of a profession, then pharmacy meets the essential requirements, which

are four in number as follows

…

2. A Representative Body of Practitioners: “The

representative body of the profession is the Royal Pharmaceutical Society of

Great Britain. The Council of the Society is elected by the members and its

functions include control over educational standards for pharmaceutical

chemists. It also guides the profession in establishing and interpreting a code

of conduct.”

If we no longer have a representative body of practitioners,

then according to Dale and Appelbe,

we would no longer meet the criteria to be considered a profession. Notably,

this section has been removed in the most recent edition, after being included in Dale

and Appelbe for at least 42

years, from at least 1979 to 2021.

The requirements for professional status in Dale and

Appelbe were set out at a time when the RPSGB served both as the regulator

and the professional body. In 2010, these functions were separated: the General

Pharmaceutical Council (GPhC) became the regulator, and the Royal

Pharmaceutical Society (RPS) became the professional body. It is difficult to

see how this changes the underlying requirement for a representative body of

practitioners, even if the representative functions of the body now reside

only with the RPS.

The examples given in Dale and Appelbe of the

functions of the “representative body of practitioners” concern the ability of

pharmacists to exert control over their own leadership within that body, and

through that control, to determine their own future, standards and education,

and to better the profession. Today, the RPS is the body which most closely

fits that description. Members elect its boards to serve their interests, and

the Assembly is appointed from within the boards; the boards and Assembly govern

the organization; and the RPS has the ability to encourage higher standards

including in respect of education. It does not have the ability to control

minimum standards or educational requirements required for registration as a

pharmacist; those functions rest with the GPhC, and are not controlled by the

profession. Only through the RPS, and not the GPhC, can the profession exert a

significant degree of control over its own future.

If the RPS transitions into a Royal College of Pharmacy, the following

consequences would arise in relation to the organization:

- It would no longer be under pharmacists’ collective control. Pharmacists, among others, may have a say, but they would not have authority over the organization insofar as, for example, they could not remove members of the most senior board – the Board of Trustees.

- It would not have an object requiring it to

represent pharmacists’ interests.

- Its governing board at the highest level in the

organization would not be elected by pharmacists.

- There would be no requirement for the Board of

Trustees to include pharmacists among its members.

- It would not control the standards of initial

education and training. This responsibility was transferred to the GPhC in

2010 and depends on government decisions. Credentialing, which the RPS can

already undertake, would still rely on recognition by employers, including

government-linked organizations like the NHS.

- Its membership numbers—if similar to those of the

RPS—would likely represent less than half of the profession.

- It would act in the interests of the public, which

may conflict with the interests of pharmacists.

In effect, there would no longer be a “representative body

of practitioners” in any meaningful sense of the term.

Later editions of Dale and Appelbe incorrectly

identified the GPhC as the “representative body of practitioners”. This was a

misinterpretation of the original text. Individuals do not become members

of the GPhC; they merely register with it, because they are statutorily

required to do so if they wish to call themselves pharmacists. The GPhC does

not represent their interests. It is not a body of practitioners through which

pharmacists can express any shared goal or purpose. Practitioners exert no

control over it and do not join it out of care or any sense of belonging, unity

or collective desire for betterment. Registration is imposed upon them. The

requirement for a “representative body of practitioners” is not satisfied

merely by having an organization registering a large number of pharmacists. For

similar reasons to those set out above illustrating the reasons that a royal

college would not be a representative body of practitioners, nor would the

GPhC.

The Core Question: Would Pharmacy Still be a Profession?

Dale and Appelbe raised a compelling point: if a group

of practitioners cannot maintain the existence of its own representative body, can

it still legitimately call itself a profession?

Claimed Advantages of Becoming a College

The current leadership of the RPS is asking you to vote in

favour of becoming the Royal College of Pharmacy. This is questionable in

itself: how can the RPS leadership be said to be promoting the interests of

pharmacists in proposing to convert the organization into one which acts in

the interests of the public instead?

The RPS leadership suggests that there are certain

advantages to the proposed transition, such credentialing and having a louder

and more effective voice for pharmacy – not pharmacists.[4],[5]

However, these are activities it could already undertake as the Royal Pharmaceutical Society. It already performs credentialing, which involves designating individuals as having reached a particular level of performance in their careers. If it seeks a louder voice, what does that entail? What prevents it from achieving that now? It already has the ability to decide its approach to engaging with other organizations and the press, and the topics it addresses. Perhaps more importantly, the college would not be providing a voice for pharmacists or pharmacy at all: it would have no objects to do so, would act for the public benefit, and to provide such a voice may conflict with this and its duties as a charity.

My view is that the advocates of becoming a royal college

are not suggesting the organization will suddenly gain new capabilities. The

point they are making is more subtle, and they have not clearly articulated it.

If the RPS becomes a royal college and a charity, it will

have a legal duty to act for the public benefit, rather than in the interests

of pharmacists as at present. This change could make the organization’s

recommendations more palatable to the government. Currently, since the RPS has

a duty to promote the interests of the profession, it could be seen to be

credentialing pharmacists to enhance their standing. However, if its duty

shifts to acting for public benefit, the credentialing it carries out may hold

more inherent value to the civil service. It is worth noting that the civil

service itself initiated this proposed transition by establishing a “Pharmacy

Professional Leadership Advisory Body”. A duty to act for the public benefit

would be consistent with the functions of the civil service.

The reason the current RPS leadership has not explained this

fully may be that doing so would involve explicitly drawing attention to the

fact that the college would be acting in the public interest rather than in the

interests of pharmacists. The implications of this significant shift have not

been clearly communicated. The lack of transparency from the RPS is a recurring

issue; for example, when the RPS announced its proposal to become a royal

college, it stated that this was partly based on an independent report

highlighting its transparency problems.[6]

Other RPS PR material related to the proposed change claims

that “the pharmacy landscape is changing rapidly” and that the

organization needs to be “stronger” (without defining what this means or

explaining how the proposed changes would achieve it) and “more flexible”

(without specifying in what way, how becoming a royal college would achieve

that, or explaining why this is necessary).[7]

These arguments are weak and are worth

noting only because they are vague and lack substance.

Finally, some may argue that a royal college would be more

“collaborative” or “inclusive” than the RPS. These terms may be used in place

of substantive arguments for change or as a means of exerting control or

suppressing dissent. Such rhetoric could discourage opposition, as critics may

fear being labelled as “not inclusive”—a term that can imply an unwillingness

to work with others. However, the RPS already has the ability to collaborate

with others. Moreover, a body representing the interests of a single profession

must, in certain respects, maintain a degree of exclusivity / non-inclusivity to

effectively fulfil its representative functions.

Limited Benefits of Royal College Credentialing

In pharmacy, several factors limit the benefits of credentialing or other

functions a royal college might perform. Control over initial education and

training, entry into the profession, accreditation of courses, and the ability

to include annotations on the register for those with postgraduate

qualifications or credentials has already been ceded by statute to the GPhC.

This constrains any role a royal college might have in setting standards.

Under the current system, there is nothing to prevent the

GPhC from considering RPS accreditations and granting register annotations for

those who achieve them. This would involve the profession establishing a

standard and determining who meets it, but GPhC approval would still be

required—just as it is now for Independent Prescribers. The GPhC’s role ensures

public protection by validating any steps taken by the RPS. If such public

protection already exists, it obviates any need for a credentialing body to be

acting for the public benefit. Consider the position of universities awarding

the MPharm degree: they are not required to act solely for the public benefit.

The GPhC provides the quality assurance in respect of University graduates.

Another limitation is that employers must value

credentialing for it to be impactful. The skills and expertise denoted by

credentials would need to align with employer needs, which might not always

align with pharmacists’ career aspirations. For example, in community pharmacy,

for businesses focused on minimizing costs, credentialing may hold little

relevance. The business model might prioritize hiring pharmacists as

inexpensively as possible, regardless of credentials. Thus, the RPS becoming a

royal college is unlikely to increase demand for credentialing among such

employers.

Modern Charters

An updated charter would likely require the RPS to operate for the public benefit, as this is a fundamental requirement of modern charters. There is no inherent positive connotation to the term “modern” here, as is sometimes implied. Modernization is only beneficial if the changes themselves are positive. It is damaging if the changes are damaging.

Organizations receiving charters today are expected to work

in the public interest. The Privy Council’s website explains:

“Their original purpose was to create public or private

corporations (including towns and cities), and to define their privileges and

purpose. Nowadays, though Charters are still occasionally granted to cities,

new Charters are normally reserved for bodies that work in the public interest.”[8]

While the RPS would not receive an entirely new charter, it would

be asking the Privy Council to materially update it, potentially mandating the

RPS to operate for the public benefit. This requirement would align with its

potential status as a charity, since a charity must act for the public

benefit. A charter that conflicted with this mandate by prioritizing other

objectives would be incompatible with charitable status.

Even if the RPS ultimately decided against becoming a

charity, a royal college might still be expected to serve the public interest

if the charter were materially updated.

Ability for Pharmacists to Control the Organization

Another important consideration is the governance structure of the proposed royal college. If the RPS becomes a royal college, pharmacist members would no longer have the authority to remove members of the most senior governing board. As a charity, this would be the Board of Trustees. Currently, RPS pharmacist members can vote for board members and replace them after three years if desired. This provides a mechanism to remove many of the members of the RPS Assembly, who are appointed from among the members of the board. The royal college would still have an assembly – renamed to the Senate – but its powers would effectively be passed to the Board of Trustees. The Board of Trustees could also decide the constitution of the Senate – so it could decide, for example, that the members of the Senate, including the President, would not be elected, or that it would be comprised entirely of non-pharmacists.

The governing board could make significant changes, such as introducing new associate membership categories, for example of pharmacy technicians. Historically, the inclusion of pharmacy technicians has been a long-term goal of some individuals pushing for the RPS to become a royal college. Some of the same individuals were proponents of the inclusion of pharmaceutical scientists in associate membership.

The number of pharmaceutical scientists who are associate

members of the RPS is low. I was once told the figure – it was of the order of

around 10 to 20, among tens of thousands of pharmacist members. Despite this,

the RPS often emphasizes “pharmaceutical scientists” in its communications,

reflecting their inclusion in its remit. More broadly, the RPS frequently

refers to its role as supporting "pharmacy" rather than

"pharmacists," as seen in its mission statement: “Our mission is to

put pharmacy at the forefront of healthcare.”[9]

On social media, immediately below its name, it states: “We are the

professional leadership body for pharmacists and pharmaceutical scientists.”

It has no duty to represent the interests of pharmaceutical scientists, but it

is clear that their associate membership influences its behaviour nonetheless.

Examination of Other RPS Charter Objects

Before considering a shift to royal college status, it is

worth further examining the RPS’s current objects.[10]

- to safeguard, maintain the honour, and promote

the interests of pharmacists in their exercise of the profession of

pharmacy.

- This object explicitly focuses on

benefiting pharmacists and upholding their professional interests.

- to advance knowledge of, and education in,

pharmacy and its application, thereby fostering good science and practice.

- This object benefits the profession

through the advancement of pharmacy knowledge, with an indirect impact on

the public.

- to promote and protect the health and well-being

of the public through the professional leadership and development of the

pharmacy profession.

- Here, public well-being is a

secondary outcome achieved through professional leadership and

development. The primary focus remains the professional interest.

- to maintain and develop the science and practice

of pharmacy in its contribution to the health and well-being of the public.

- This object acknowledges the public

benefit of developing pharmacy science and practice but keeps the

profession central to its mission.

Each of these objects prioritizes the profession and its

members, with public benefit as an associated outcome. This is fundamentally

different from the proposed royal college objects, which would directly

prioritize the public benefit.

RPS Assets

Consider the implications for the RPS’s assets under its existing charter:

“4. The income

and property of the Society shall be applied solely towards the promotion of

the objects.”

If the RPS becomes a royal college, the assets it has

accrued over many years—through the contributions of pharmacists—would no

longer be put to use for their direct benefit. Instead, these assets would be

given over to the royal college as a charity, and redirected toward serving the

public. While they would still support the organization’s stated objects, those

objects would have shifted to prioritize public benefit rather than the

interests of pharmacists.

The Name of the Organization

The proposed name for the new royal college—The Royal College of Pharmacy, not The Royal College of Pharmacists—offers

a significant clue about the intentions of those advocating for this change.

Consider the naming conventions of other royal colleges associated with

healthcare professions. With two exceptions—the Royal College of Nursing (RCN), which has an older charter requiring it to act in the interests of nursing and midwifery professions, and the Royal College of Emergency Medicine,

which serves Emergency Physicians—these organizations are typically named after

their professions. Examples include the Royal College of Physicians, the Royal College of

General Practitioners, the Royal College of Radiologists, and others.[11]

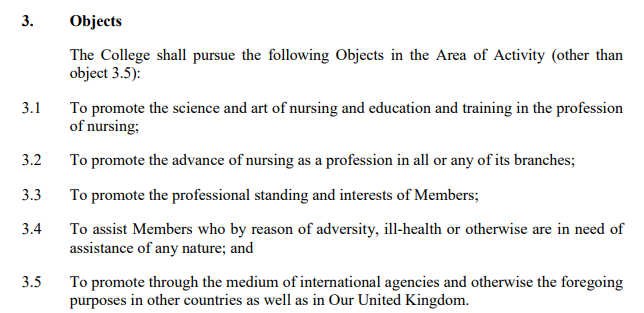

The objects of the RCN charter are shown below.

“Pharmacy” is a scientific field. It is also an area of

study, a field of practice, and a type of business. It is not the noun that

specifically refers to the profession as a group of people—pharmacists. The proposed name, therefore, raises the possibility

that the new royal college may be subject to influence from various external

entities, such as pharmacy businesses, universities, the pharmaceutical

industry, and wholesalers. A royal college would act “for the public benefit”,

and to varying degrees, each of these types of organization serves the public

interest. The voice of pharmacists within the college could be very much drowned out among these

competing voices.

You can be confident that the Royal College of

Pharmacy will not limit its membership to pharmacists for very long. While

proponents may claim that there are no immediate plans as part of this change to

expand membership beyond pharmacists, history suggests that this would change

soon after the ink is dry. Pharmaceutical scientists have already been given

associate membership, and it is only a matter of time before pharmacy

technicians and potentially other groups are added.

It is clear from the proposed charter that pharmacists would

be unable to prevent the Board of Trustees from adding new associate membership

groups. It provides, under article 7:

“(2) The Board of Trustees may establish one or more

categories of associate membership, but such Associate Members are not Members

of the College for the purposes of this Our Supplemental Charter.”

(3) Subject to this Our Supplemental Charter, Members and Associate Members of the College shall have such rights, privileges and obligations (and may be charged such subscriptions) as may be specified in Regulations.

If an organization represented both pharmacists and pharmacy

technicians, it would create an irreconcilable conflict of interests. These

groups compete over costs, roles, and responsibilities. Pharmacy technicians

have recently been authorized to deliver PGDs (Patient Group Directions), and a

substantial consultation in 2024 proposed allowing them to supervise the sale

and supply of medicines.

However, an organization serving the public interest would represent neither of these groups. If the royal college prioritized the public interest, its decisions may well align with the preferences of the civil service. Should the civil service determine that pharmacy technicians should take on additional roles, the royal college may comply, producing compliant corresponding policy. Similarly, if it decided that pharmacists should perform specific tasks, the royal college may be keen to follow suit.

Member Duties to the Charity

Members may potentially have a duty to act in the best interests of the charity, for example when exercising their voting powers. The Charity Commission has taken this view for many years - see RS7 - Membership Charities at pages 18 and 34 (https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/membership-charities-rs7). In turn, the charity acts for the public benefit. Some may argue that members would have a duty to vote in a way which increase the charity's revenue, for example by introducing new members.

The juxtaposition of the current position with the proposed one is striking: currently the RPS has an object to promote the interests of pharmacists. As a college, members may find themselves with a duty to act in the best interests of the organization.

In Everyone Else’s Interests but Pharmacists’?

If pharmacists lose an organization that advocates for their

interests, who will oppose policies that work against them? If other

stakeholders decide to impose unfavourable conditions on pharmacists, they will

face less resistance if the RPS cannot even theoretically stand in their way.

Contractors as contractors, for instance, are unlikely to oppose the

transition. They may even support it, recognizing that a royal college focused

on the public benefit may be less likely to challenge the conditions imposed on

pharmacists than an organization which is meant to act in pharmacists’

interests.

Similarly, the civil service has no incentive to oppose the

change. At present, the RPS is a body that can challenge civil service

proposals. For example, under Martin Astbury's presidency, the RPS resisted

certain pharmacy supervision proposals from the Department of Health and Social

Care (DHSC). If the RPS becomes a royal college, this capacity for resistance

diminishes, making it easier for the civil service to implement its policies

without opposition.

Unions and indemnity insurance providers may also be

unlikely to object. Historically, there has existed the possibility that the

RPS would become a union or an indemnity insurance provider, creating

competition in the sector. However, a royal college acting for the public

benefit, particularly if it also becomes a charity, would not do so. The risk

of competition would fall away if the transition to a royal college went ahead.

Whose Interests Should the RPS Serve?

Some might argue that acting for public benefit aligns with their

own motivations as a pharmacist. After all, pharmacists work to serve the

public. However, that does not mean the professional body should prioritize the

public interest over pharmacists’ professional interests. The role of a

professional body is to represent and advocate for its members.

Some might think, "But I’m a member of the public

too!" While this is true, in their capacity as a pharmacist, they require

a professional body to act specifically in their interests. Many organizations

already work to serve the public. A counterbalance is necessary: a body that

speaks solely for the profession. Currently, the RPS serves this role.

If the RPS transitions to a royal college, this critical

balance is lost. It will no longer act as a voice for pharmacists, leaving pharmacists

without the organization’s much-needed representation.

In What Ways Could the Professional and Public Interest Conflict?

Consider the situations in which the interests of the public

might conflict with those of pharmacists. The Assisted Dying Bill provides a clear illustrative example. From the

public's perspective, Parliament might deem it beneficial for assisted dying to

be available, provided adequate protections are in place. Public sentiment

might support requiring pharmacists to sell or supply the necessary drugs.

Alternatively, the public might expect pharmacists to refer patients to someone

else who can provide these drugs, even if the pharmacists themselves object on

ethical grounds.

Pharmacists, however, might object to participating in

assisted dying, whether directly or indirectly. Their objections could stem

from ethical, religious, or societal concerns, such as a belief that palliative

care should be prioritized and improved rather than offering assisted dying as

an option. These objections could place pharmacists in an ethically fraught

position if they are required to supply the drugs or refer patients to others

who will.

The RPS took a position saying that pharmacists should be

able to exercise conscience, and should not be put under any duty to refer to

someone else would provide the service.[12]

It said:

“Conscience clause - It is a

pre-requisite that a conscience clause is incorporated into any legislation.

There must be no obligation for any pharmacist to participate in any aspect of

an assisted dying or similar procedure if he or she feels this is against their

personal beliefs. The framework we are proposing allows pharmacists to ‘opt in’

by completing the necessary training, rather than ‘opting out’. It also avoids

the need for anyone ethically opposed to assisted dying to signpost to another

pharmacist as this can also pose an ethical dilemma.”

However, if the RPS were to become a royal college with a

duty to act for the public benefit, it might adopt a different stance. For

example, it could advocate for a duty requiring pharmacists to provide the

service or at least to refer patients onward, creating a conflict between

pharmacists' professional autonomy and the perceived needs of the public. The

college’s proposed objects include relieving sickness.[13]

The Board of Trustees, which may be comprised partly or entirely of

non-pharmacists and in any event would be required to fulfil the role set out

in the object, may consider that this requires them to adopt a different

position on assisted dying to that advanced by the RPS.

Another example of potential conflict is the matter of

professional remuneration. Pharmacists may seek higher fees for their services,

while the public—and by extension, government policymakers—may favour

delivering those services as cheaply as possible. This could lead to tasks

being delegated to pharmacy technicians or other less-qualified personnel to

reduce costs. A royal college acting in the public interest might support these

cost-saving measures, even if they are detrimental to pharmacists’ professional

and financial interests. Such actions would align with the interests of

businesses and the civil service, but not necessarily those of pharmacists.

A Royal College As Well?

Having a royal college could offer benefits to the public,

such as credentialing potentially having a higher value, and standard-setting

within the profession. However, an increased focus on credentialing could also

have drawbacks. If employers began requiring specific credentials from

pharmacists, membership of the royal college might become mandatory, or

effectively mandatory. This would increase costs for pharmacists, as they would

need to pay membership fees to the college in addition to their registration

fees with the GPhC. Despite this financial burden, wages might not

increase to offset the additional costs. It would benefit the public to have

better services at lower cost.

Furthermore, if the RPS becomes a royal college, its

financial stability might depend on its ability to compel pharmacists to obtain

credentials through the college. The college could charge for credentialing

directly, or increase general membership fees. To ensure a steady revenue

stream, the college would have an interest in encouraging employers to require

these credentials, forcing pharmacists to join and pay for membership and/or assessments.

While there are potential benefits to having a royal college

in terms of advancing professional standards, forming such an institution by

transforming the RPS raises significant concerns. If the RPS becomes a

royal college, pharmacists would lose their current professional representative

body. Surprisingly, the RPS has not addressed this issue in its proposals,

leaving a critical gap in the discussion.

The RPS does not appear to have set out to inform pharmacists of

the risks and adverse consequences of the proposed transition. Instead, it has

chosen to campaign solely in favour of the proposed change.

It is worth considering whether a Royal College of Pharmacists or a similar institution could be

created separately, leaving the RPS intact to continue representing

pharmacists’ professional interests. However, simply transitioning the RPS into

a royal college—particularly a college of pharmacy, which may prioritize

the broader field over the profession—risks leaving pharmacists without

effective representation.

What Should be Done?

A consideration with having a royal college in pharmacy is

that we already have a royal body, the Royal Pharmaceutical Society, and it is

our professional representative body. Would it be problematic to have both the

Royal Pharmaceutical Society and a Royal College of Pharmacists?

Rather than rushing to support the RPS’s transition into a

royal college, it’s vital to consider the broader implications. If a royal

college was to be established from the RPS, the profession should consider whether

it could simultaneously create a new representative body for pharmacists.

Without this, pharmacists would be losing a voice in critical areas such as

wages, working conditions, and professional autonomy.

The creation of a new representative body for pharmacists

would require careful consideration. The RPS has a charter conferred by the monarch,

facilitated by the privy council. To that extent, its operations and governance

have been subject to scrutiny and approval, which to an extent adds gravitas to

its activities and provides a degree of assurance. It occupies a unique

position at present, in that the civil service often includes it in discussions

about policy change affecting the profession. If it did not, it would not be

seen to have consulted the profession.

It would not be possible to create another organization with

the same position and status as the RPS, once the RPS ceased to exist in its

current form. A modern royal charter would not allow such an organization to

operate in the same way, and in any event there has been no suggestion of

creating a second organization with a royal charter. If one was going to

recreate the RPS, then why change the RPS to a royal college in the first place?

Relative to the role of the RPS, the roles of other existing

organizations in pharmacy are limited in scope (for example, to defence rather

than active representation), and the civil service often appears not to want to

listen to them. It does not include them in key policy discussions. It may say

that it has no reason to, where it is engaging with the RPS, because it is

already listening to the profession. In future, it is possible that it would

seek to engage only with a royal college, pretending that this is the mechanism

by which pharmacists’ views are represented, but leaving pharmacists with no

representation of their interests to government.

The civil service has to act in the public interest; it is

not its role to identify or ensure professional representation for pharmacists.

There is little wonder that it has demonstrated little if any care, in the

process which has led to the present proposal, for whether pharmacists retain

representation of their own interests. That is not its concern.

A thoughtful and transparent discussion is needed. Proposals

for a Royal College of Pharmacists or similar institution could be

discussed alongside plans for maintaining a professional representative body.

This approach would ensure that pharmacists would not lose their representation

or find themselves paying higher fees without corresponding benefits.

Until these issues are addressed, in my view it will be prudent

to vote against the current proposals to transform the RPS into a royal

college. Doing so will better protect pharmacists’ professional interests and help

to ensure that the conversation moves in a direction that benefits the

profession as a whole.

Whose Interests Should a Professional Body Represent?

There is research and other discourse which has considered the question of

whose interests should be represented by a professional body. Some of this

dates back to times where it was common for the same organization to function

as the regulator and the professional body (see for example a paper by Harvey

and Mason in 1995[14]).

That used to be the case with the RPSGB before it was renamed to the RPS and

became solely the professional body, and a separate regulator – the General Pharmaceutical

Council – was created. The

RPSGB was both the regulator meant to act in the interests of the public, and

the professional body meant to act in the interests of the profession. There

was an obvious conflict. It was for this reason that the RPSGB’s functions were

split. The RPS’s present proposal is that both bodies created by the split will

ultimately serve the public – some may view this as an unfair outcome

for pharmacists!

Some of the discourse which examines whether a professional

body should represent the interests of the public or those of the profession reaches

conflicting conclusions. Some older research papers are likely to have been

affected by the fact that they've had to consider professional bodies working

with a dual role. Further, in reaching conclusions, where consideration has

been given to the extent to which the professional body should serve the

interests of the public, it is recognised that such service by a professional

body would be indirect, ultimately with the intention or objective of serving the

interests of the profession.

It has been posited that in serving the public, the

profession will ultimately serve its own interests because it will be seen to

be acting with selflessness and altruism, which will increase the prestige and

trustworthiness of the profession. This perspective, however, seems a flawed way

to look at the function of a professional body. The profession should

act with selflessness and altruism in its work, and it has a regulator which

requires it to do so. The professional body will be aware of this. But through

its professional body, it should have an organization looking after its

interests directly. Further, the aforementioned posited contention is naïve, in

that it does not take into account the potential for interference from those

with vested interests, and corporate capture (where businesses use their

political influence to take control of the decision-making apparatus of an

organization).

In considering the question “in whose interests should the

professional body act directly?”, it would not make sense for the answer to be “the

public’s” and the benefit to the profession being sometimes a side effect, if

the ultimate intention is to serve the professional interest. In such a case,

where the interests of the public and the profession conflict, it would always be

the interests of the public which would win out. The profession would have to

take a back seat – its interests would be secondary. It might be the case that

in acting in the interests of the profession, a professional body would offer some

consequential benefit to the public because, for example, in increasing the

standards of education and training, whether that be initial or postgraduate

education and training, that would result in a higher overall level of skill

and competence from which the public would benefit. It should be viewed from

that perspective rather than the opposing one. Which other organization is

going to act in the interests of the profession, if not the professional

body?

One limitation of the research I’ve encountered is its

narrow focus on specific functions of professional bodies, such as raising

educational standards. While educational standards are undeniably important,

other crucial functions often receive limited attention. These may include:

- The provision of professional indemnity insurance

- The services of a trade union

- Offering professional advice

- Responding to political developments

- Interfacing with the media

- Liaising with policymakers and MPs

- Raising the profession’s profile

A professional body acting solely in the public interest

would struggle to perform many of these functions effectively, as they may not

align directly with the public interest or might even conflict with it. For

instance, advocating for better pay or working conditions for pharmacists may

not always be seen as benefiting the public, but it is critical for the

profession’s well-being.

There is also the question of whether the conflict of

interest between being a regulator and a professional body is so significant that

it warrants their separation, balanced against the benefits of having

professional expertise within the regulator. While this debate is valid,

Parliament has already determined that the two functions should remain

separate. For the civil service to suggest that both the regulator and the organization

which is currently the professional body should act solely in the public

interest goes a step too far. If both bodies serve the public, what remains to

protect and promote the profession’s interests?

How Should the RPS have Reacted to the UK Pharmacy Professional Leadership Advisory Board?

The Royal Pharmaceutical Society (RPS) holds a relatively

strong position within the profession. In my view it should have maintained

independence from the UK Pharmacy Professional Leadership Advisory Board (UKPPLAB),

responding to its recommendations with an acknowledgment that professional

leadership must ultimately be decided by the profession, not the civil service

or its appointees. By participating in UKPPLAB, the RPS positioned itself as

subordinate to the board and lent its credibility to the UKPPLAB – though it

was perhaps influenced by a desire to preserve its own standing and avoid embarrassment.

This is of no disrespect the civil service. When it comes to

professional leadership, the RPS is the existing body representing the

profession—not an entity created by the civil service. Some may view the Chief

Pharmaceutical Officers (CPhOs) who established UKPPLAB as senior figures whose

input must be heeded. Within the civil service hierarchy, this may be true.

However, as members of the pharmacy profession, their opinions are no more or

less valid or important than those of any other pharmacist. Professional

leadership should not be determined by civil service appointees, but by the

profession itself.

The RPS should in my view have asserted its independence by

declining to participate in UKPPLAB meetings, instead stating, for example: “We

appreciate your recommendations, but the leadership of the profession must be

determined by the profession, not the civil service or its representatives.”

Had the RPS taken this stance, the UKPPLAB’s recommendations

would have carried the appropriate weight. They’d have been recommendations,

and no more. Instead, by joining the board, the RPS allowed itself to be

influenced, potentially compromising its role as the profession’s advocate.

Could the Royal College Receive Charitable Donations From Pharmacy Contractors, Wholesalers and Pharmaceutical Manufacturers, for example?

Yes.

An example of this can be seen in the case of the Royal

College of General Practitioners, here: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2025/01/11/royal-college-of-gps-conflict-childrens-covid-jabs

Two quotes from the article:

·

“However, Prof Marshall failed to declare

that the Royal College had previously received payments from Pfizer, the only

pharmaceutical company at the time with a Covid vaccine authorised for use in

children.

Prof Martin Marshall

Prof Martin Marshall, who was chair of the

Royal College of GPs at the time of the pandemic and spoke at a key meeting

During 2021, it received more than £100,000 from

Pfizer, according to the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry

(ABPI).

Their register shows that during that calendar

year, £102,820 was given for “donations and grants” as well as “benefits in

kind”.

This was more than double what the organization

received the previous year from Pfizer –

£49,324 – and up from £4,309 in 2019 for event sponsorship, donations, grants

and benefits in kind.”

·

“A spokesman for the Royal College of GPs,

said: ... “The College’s income from Pfizer for the year ending March 31 2022

was related to educational resources on migraine and arthritis, amounting to

0.26 per cent of total RCGP income, and had no bearing on discussions related

to the pandemic.””

Could such donations influence the behaviour of the

organization? A more incisive question might be: What Board of Trustees is likely

to act in ways that could alienate or offend its major donors?

Use of Members’ Funds

One of the proposed objects of the royal college, set out in

the proposed charter, is:

“(c) to relieve poverty, financial hardship or other

distress among current and former Members and Associate Members of the College

and development of the pharmacy profession;their dependants and among those

studying or training to be a pharmacist, and such others who practice or

have practised the profession of pharmacy as the Trustees may determine from

time to time.”[15]

(Emphasis added).

Various questions arise from this object, including:

· How would the Board of Trustees define “others

who practice or have practised the profession of pharmacy”? Would they

interpret this as including pharmacy technicians and dispensing assistants

(again the accuracy of this interpretation would involve a separate debate),

and if so would this object allow the Trustees to give away the college’s

funds, including those derived from pharmacists’ membership fees, to non-pharmacists?

· What would be the implications for Pharmacist

Support – a charity which already exercises some of these functions?

Appointment of Trustees

The Board of Trustees will be appointed in accordance with

Regulations created by the Board of Trustees. The trustees may or may not be

pharmacists – there is no requirement specified in the proposed charter in this

regard.[16]

The RPS has suggested that the chair of the Board of Trustees – the chair being

the most senior position in some respects – may be a non-pharmacist, because it

requires substantial expertise in running a charity.[17]

The RPS has also expressed the “intention” that the Board of Trustees would

include a majority “drawn from the profession” – though the RPS does not say

whether it considers “profession” to be a reference solely to pharmacists, there

is nothing to provide for this within the charter, and it would be beyond the

control of the RPS. The Board of Trustees would decide this for itself. It would

be entirely within its control to decide that it should be comprised entirely

of non-pharmacists.

The “Save Our Society” Campaign

In 2003, the RPSGB proposed a new royal charter which amongst other things would have required the organization to operate in the context of the public benefit (though safeguarding, maintaining the honour and promoting the interests of pharmacists was retained). The current proposal goes further than this - the college would be entirely for the public benefit and the aforementioned object relating to pharmacists would be deleted.

The proposals in 2003 led to the “Save our Society” campaign. Four individuals brought a legal

challenge, which led the privy council to put the RPSGB Council’s proposals on ice

(see Koziol et ors. v Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain et ors.

[2004] EWHC 1254 (Ch)). As I understand it, the delay also allowed the

campaigners to field candidates who opposed the changes for election to the

RPSGB Council. Such candidates were ultimately elected, leading to the defeat of

the proposals. Against this historical backdrop, it was interesting that the

RPS cancelled its board elections for 2025.[18]

Questions Asked by the Guild of Healthcare Pharmacists

The Guild of Healthcare Pharmacists asked questions about

the proposed transition, in a letter dated 21 October 2024.[19]

These included, “In recent history Royal Colleges and the leadership of

Royal Colleges have come under intense scrutiny and criticism in medicine

during the discourse surrounding Physician Assistants/Physician Associates.

Junior/resident doctors make the point that Royal Colleges appeared to be

primarily enacting the aims of government as opposed to leading the medical

profession forward. With these fresh issues in mind, what safeguards would be

put in place to ensure that a Royal College of Pharmacy truly led for, and

on behalf of, the pharmacy profession?” (Emphasis added.) Following the

publication of the proposed charter for the royal college, it is now apparent

that the royal college would not be led for or on behalf of the

profession at all; it would be operated for the public benefit.

Special Resolution Ballot - What Majority would be Required?

(section added 20 March 2025)

The current Charter and Regulations can be found at

https://www.rpharms.com/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=P4j2CrhkWMo%3d&portalid=0

and

https://www.rpharms.com/Portals/0/RPS%20document%20library/Open%20access/Regulations/NEW%20REGS%20CURRENT_%20WITH%20AMENDMENTS%20RE%202025%20ELECTIONS%20-%20modified%20version%2014_02_25.pdf

respectively.

The RPSGB Assembly can make regulations (“Regulations”) pursuant to the power in Article 10 of the Charter.

Insofar as any Regulations contradict the Charter, the Charter will prevail. Insofar as they do not, the Charter gives the Regulations the same force as the Charter itself.

Article 11 of the Charter provides:

“The Society may by Special Resolution amend, add to or revoke any of the provisions of this Our Supplemental Charter or of any further Charter granted to the Society, or may amend the name of the Society, provided that any such amendment, addition or revocation or name shall not be effective unless approved by Us, Our Heirs or Successors in Council.”

Article 12 of the Charter provides, so far as is material:

""Special Resolution" means a resolution of the Assembly confirmed by a ballot of the members referred to in articles 5(1)(a) and 5 (1)(b) by not less than a two-thirds majority of the votes of such members."

The members referred to in articles 5(1)(a) and 5(1)(b) are those who are pharmacist and former pharmacist members of the RPS.

The ballot threshold in Article 12 could be interpreted as either:

i. The eligible members have votes. Two thirds of those votes must be cast in favour. As such, two thirds of all those members eligible to vote must have cast their vote in favour. (“The First Interpretation”)

ii. Of the votes cast, two thirds must be in favour. (“The Second Interpretation”)

There are good reasons as to why the First Interpretation is correct. However, even if the Second Interpretation were correct, the Regulations – at the very outset – require two thirds of eligible voters to ratify changes to the Charter.

Regulation 1.1.1 provides inter alia:

“Royal Charter

…

Any changes to the overall content of the Charter, including to the composition of the Assembly, or the creation of any additional categories of membership of the Society require a Special Resolution to be passed with the support of at least 2/3 of the Members and Fellows eligible to vote.”

If the Second Interpretation were correct, Regulation 1.1.1 would create an additional requirement, but not a contradictory one. For the vote to go ahead:

a. two thirds of those eligible to vote would have to vote in favour, and

b. two thirds of the votes cast would have to be in favour.

Both of these requirements would be satisfied if two thirds of those eligible to vote, voted in favour.

Regulation 3.4 provides, in the context of meetings (this being the heading for Regulation 3):

“‘Special Resolution’ means a resolution of the Assembly confirmed by a ballot of the members eligible to vote (ie Members and Fellows, currently in good standing) giving a two-thirds majority of the votes cast.”

Regulation 3.4 would not apply to the current ballot, because it is not being conducted in a meeting. It is otherwise in any event immaterial considering the effects of Article 12 and regulation 1.1.1. Again even if the Second Interpretation were correct, 1.1.1 would create an additional requirement irrespective of the requirements of 3.4.

Conclusion

The RPS should have presented alternative perspectives to pharmacists – that would have been acting in their interests. I hope this article helps some in making their decision on how to vote. For the reasons above, I will be voting against.

Last updated: 23 March 2025

[1]

https://www.rpharms.com/Portals/0/RPS%20document%20library/Open%20access/Governance%20documents/text-of-the-2004-supplemental-charter-as-amended-27.09.10.pdf?ver=2016-11-08-094856-680

[2]

https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2011/25/section/2

[3]

https://www.rpharms.com/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=FwL02tnOxNI%3d&portalid=0

[4]

https://www.rpharms.com/about-us/changeproposals/changefaqs

[5]

https://www.rpharms.com/Portals/0/RPS%20document%20library/Open%20access/Guidance/Roadshow%20Report_10_01_25_single%20pages.pdf

[6]

https://www.rpharms.com/about-us/changeproposals/changefaqs

[7]

https://www.rpharms.com/changeproposals/

[8]

https://privycouncil.independent.gov.uk/royal-charters/

[9]

https://www.rpharms.com/about-us

[10]

https://www.rpharms.com/Portals/0/RPS%20document%20library/Open%20access/Governance%20documents/text-of-the-2004-supplemental-charter-as-amended-27.09.10.pdf?ver=2016-11-08-094856-680

[13]

https://www.rpharms.com/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=FwL02tnOxNI%3d&portalid=0

[14]

http://www.qualityresearchinternational.com/Harvey%20papers/Harvey%20and%20Mason%20Professions%201995%20[2014].pdf

[15]

https://www.rpharms.com/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=JbvxgNWBFMs%3d&portalid=0

[16]

https://www.rpharms.com/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=JbvxgNWBFMs%3d&portalid=0

[17]

https://www.rpharms.com/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=lJoIh8PWtGA%3d&portalid=0

[18]

https://pharmaceutical-journal.com/article/letters/raising-concerns-about-the-cancellation-of-2025-board-elections

[19]

https://www.ghp.org.uk/an-open-letter-rps-royal-college-proposal/